Having moved frequently throughout my life, I’ve noticed a recurring pattern: the streets I’ve lived on are often named after individuals who gave their lives for a cause, usually their country.

In Germany, many of the streets where I’ve lived are named after individuals who died pursuing a global revolution. In Italy, I lived on a street named after a man who convinced others that dying for the nation was a noble act. England was a different story. There, I lived on a street named not for sacrifice or conviction, but for lineage. It bore the name of a noble family that had lived in the area for nearly a thousand years—honored not for ideals, but for enduring wealth and presence.

The name of the street where I grew up was always a source of pride for me.

In the early hours of March 27, 1941, a coup d’état overthrew the Yugoslav Royal Government. Just two days earlier, that government had signed the Tripartite Pact—a non-aggression agreement with the Axis powers. Now, the government was gone.

Hitler responded immediately by ordering the invasion of Yugoslavia.

With the carefully planned invasion of the Soviet Union scheduled for the summer, and Italian efforts in Greece falling short, any potential threat to German positions from the southern flank—namely, Yugoslavia—had to be neutralized.

Shortly before midnight on March 27, the German ambassador in Rome received a message from Hitler for the Duce, with instructions to deliver it 'this evening.' Ambassador Hans Georg von Mackensen met with Mussolini at 02:00 on March 28. By 04:00, Hitler had received Mackensen’s report: Mussolini had agreed to all of Hitler’s demands.

Italy began preparations to invade Yugoslavia and target its naval forces. On April 6—just ten days after the new Yugoslav government had taken power—the country was attacked from all sides, except along its short border with Greece. Hopes that Yugoslavia might mirror the Serbian army’s heroic resistance from the First World War quickly proved futile.

Overwhelmed by Axis forces, the country fell within days. The act of capitulation was officially signed on April 17, 1941.

By the evening of April 14, 1941, news had reached the Bay of Kotor that Yugoslavia was on the verge of surrender. Among the first to receive it was the destroyer Zagreb, one of the newest ships in the Yugoslav Navy.

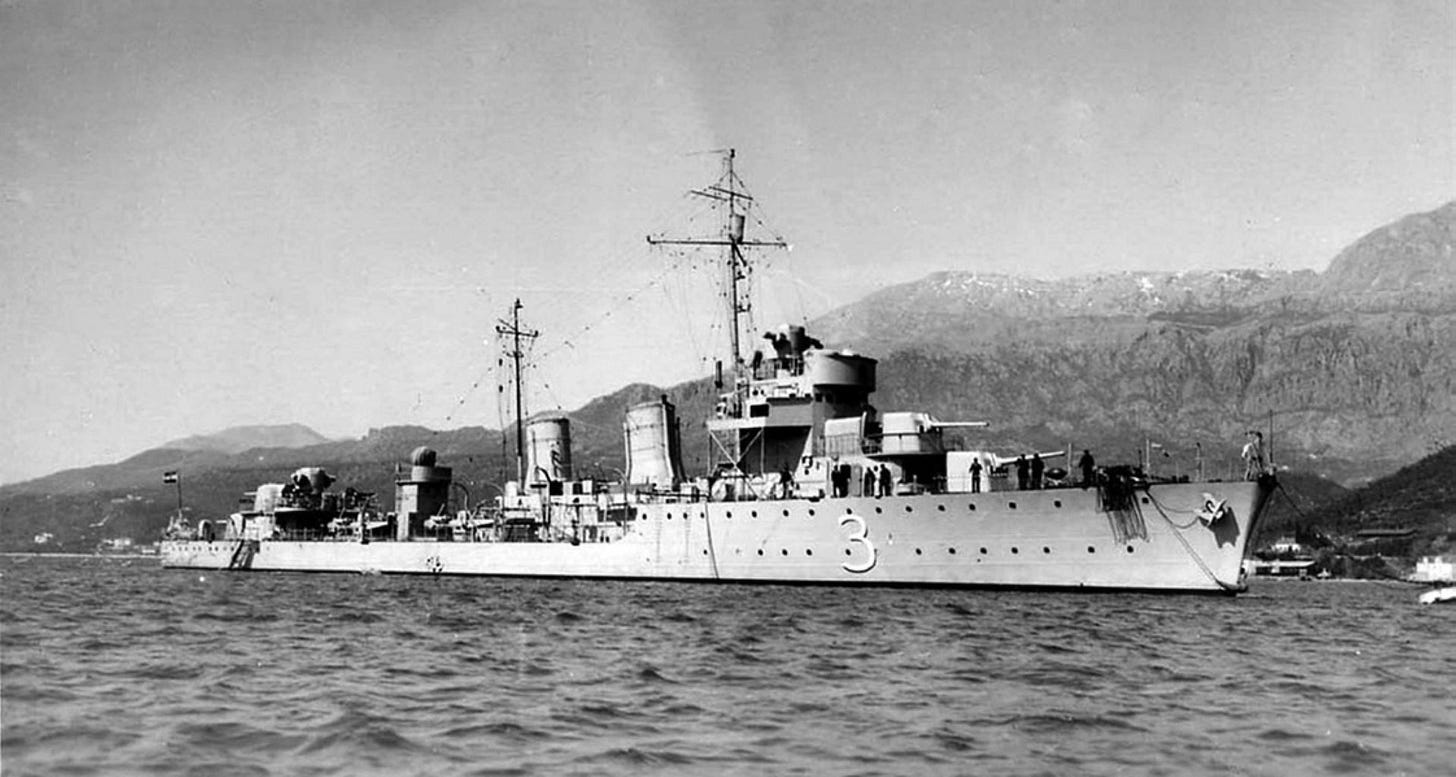

Zagreb in the Bay of Kotor before the war. Note the Cyrillic 'З'—the port side bore a Latin 'Z,' symbolizing equality between the two alphabets. (Zagreb = Загреб). (© Wikipedia)

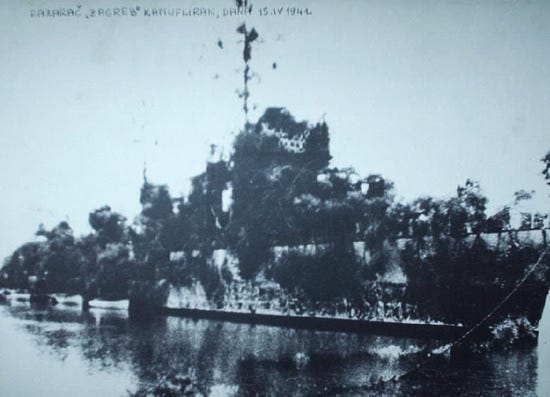

Zagreb in full camouflage, April 15, 1941. Nikola Safonov took this last known photograph of the ship.

Yugoslav soldiers were ordered to surrender in accordance with the specific demands of the Axis powers and instructed not to destroy any military equipment. On the morning of April 17, Italian ships began to appear nearby. Morale aboard Zagreb collapsed, and the ship’s captain, Nikola Krizomali, ordered the crew to abandon the vessel and hand it over to the approaching Italian officers.

But two officers from Zagreb had different plans.

Milan Spasić (from Belgrade) and Sergej Mašera (from Gorizia) knew each other from the Dubrovnik Naval Academy, where they studied together.

Sergej Mašera and Milan Spasić (© Wikipedia)

Aboard Zagreb, Lieutenant Commander Milan Spasić was responsible for torpedoes and mines, while Lieutenant Commander Sergej Mašera served as the ship’s artillery officer.

In 1941, just before the outbreak of war, much of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s naval force was stationed in the Bay of Kotor. Zagreb, along with Belgrade, Ljubljana, and the flagship Dubrovnik, formed the First Torpedo Division.

Spasić and Mašera had reunited aboard Zagreb after completing their training at the Naval Academy, where they had been commissioned in late 1940 and early 1941, respectively.

Milan Spasić was the first 'continental'—a term for someone from the non-Adriatic regions of Yugoslavia—to graduate from the Naval Academy with top honors.

When the Axis invasion began, Yugoslav naval units and their bases came under relentless bombardment. Through a combination of evasive maneuvers and anti-aircraft fire, the destroyers managed to avoid direct hits—and even succeeded in downing a Stuka dive-bomber.

But the most damaging blow the Yugoslav destroyers received was not physical, but psychological. News of the proclamation of the Independent State of Croatia and reports of the imminent surrender of Yugoslav forces had a devastating impact on morale. Sailors began abandoning their posts.

British naval and intelligence officers stationed in the Bay of Kotor attempted to organize the departure of Yugoslav vessels toward British-held positions in Greece and the broader Mediterranean, aiming to prevent the ships and their equipment from falling into enemy hands.

In the conditions of chaos, desertion, and lack of morale, only the submarine Nebojša and the torpedo boats Durmitor and Kajmakčalan managed to escape.

Rather than obey their captain’s orders, Spasić and Mašera made the fateful decision to scuttle the ship.

In the morning of April 17, Captain Krizomali ordered the crew to abandon Zagreb and surrender it to the approaching Italian forces. According to surviving testimonies, Lieutenants Spasić and Mašera engaged in a heated argument with the captain over this decision.

Last surviving photographs of the Zagreb crew. Mountain Vrmac is visible in the background.

This is a rare wartime photo from Zagreb. Smiling Lieutenant Mašera (with headphones on the right) is alongside his artillerymen.

When Captain Krizomali began organizing the abandonment of the ship, Mašera and Spasić made their decision: they would stay behind and scuttle Zagreb. They placed explosives in the torpedo tubes and ammunition chambers

Just before midday on April 17, 1941, a rapid one-two burst of detonations rips through the vessel’s hull, shredding steel plates and sending shockwaves the length of the deck; within moments, the once-stalwart ship fractures, erupts in flames, and, its buoyancy gone, sinks nose-first until it lands with a dull, final thud on the shallow seabed.

The remains of Zagreb. The ship was later salvaged during the war to use the metal for the purposes of the military industry.

Mašera might have been partly motivated by his anti-Italian feelings, given that his family was forced to leave his hometown of Gorizia after the First World War, when the Kingdom of Italy took over the former Austro-Hungarian city.

It remains unclear whether the two men chose to remain on the ship as a symbolic act, or whether their presence was necessary to ensure the explosives detonated—either because of the proximity of Italian troops or the volatile nature of the materials themselves.

Caught at the center of the blast, the two officers have no chance to react and are killed instantly. The following day, fishermen found the corpse of Milan Spasić in the sea. He was buried in the cemetery of the nearby Serbian Orthodox Savina monastery. As a way of paying respect, several Italian officers attended the funeral. Mašera’s body was not found, yet his name was written next to Spasić's.

There is one Ivo Andrić sentence I love to quote:

Perhaps the true tragedy of heroism lies in this: not in the brief pain or the liberating death, but in the fact that the hero, by his deed, crosses that fateful line separating him from ordinary people and the everyday order of things. He is left alone, without kin or friend, stripped of all personal identity, and becomes what future generations desire and what the times make of him.

The Royal Yugoslav government, operating in exile, celebrated the actions of Spasić and Mašera. However, with the formation of a new Yugoslavia in 1945, a different kind of hero was sought, one that was necessarily tied to the communist party.

Although communist Yugoslavia glorified martyrdom in the fight against occupying forces, these two courageous naval officers were, above all, products of the former royalist Yugoslavia. The new regime acknowledged their sacrifice, but only very cautiously and with restraint.

Yet this archetypal story of courage and martyrdom lived on, even if it took time for Spasić and Mašera’s sacrifice to receive full recognition.

In 1968, French director Alexandre Astruc made a film based on their actions, Flammes sur l'Adriatique (marketed in English as Flames Over the Adriatic). The film was a Franco-Yugoslav co-production, with the screenplay written by renowned Yugoslav author Meša Selimović.

It's a shame that Flames over the Adriatic is not really a good film. One unbroken scene that lasts several minutes, depicting intensive scenes from the ship's interior, manages to get near the claustrophobic intensity of scenes from Das Boot. Still, it's mostly a dreadful watch.

The film helped bring the names of the two officers back into the public sphere—or, one could say, it marked the beginning of a more permissive memory culture. In the 1970s, Spasić and Mašera were posthumously awarded the Order of the People's Hero (Orden narodnog heroja).

Spasić and Mašera joined the list of approximately 1,300 People's Heroes of Communist Yugoslavia, and to the best of my knowledge, they remain the only serving servicemen of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia to be included on that list.

Current state of Spasić’s grave near Savina Monastery. Some of Mašera’s remains were discovered by divers in the 1980s and were subsequently transferred and ceremonially buried in Slovenia. (YouTube screenshot)

After Spasić and Mašera were posthumously recognized as People's Heroes in 1973, this opened the door for wider recognition across Yugoslavia. Streets were named after them in numerous Yugoslav cities, including the street in Belgrade where I grew up. Sadly, the street named after Sergej Mašera in Zagreb was renamed in the 1990s.

I am pretty proud of my childhood street.