Imagine that a time machine exists.

Picture a Belgrader named Kosta, a junior civil servant in his late twenties, strolling through the city center in the spring of 1905. Lost in thought, he accidentally falls into a hole and, upon getting up, finds himself in the heart of Belgrade’s urban jungle in 2025.

What thoughts would cross his mind? What might astonish him? Would he notice similarities with his own time?

Naturally, he would be astonished by the technological advancements, immense population growth, and tall skyscrapers.

However, it is essential to consider: what would he perceive regarding society? How would he view the state's operations, the individuals he encounters on the street, and the realms of politics and culture?

He spots a cafe and grabs a chair.

After disappointedly realizing what a “self-serving“ system is, he goes and gets himself a cup of coffee. After taking a few sips, he begins to eavesdrop on the conversations happening nearby. He would listen to discussions about the war in Ukraine, speculations about Trump’s future actions, and the latest whispers from Serbian politics. At the beginning of the 20th century, Serbs closely monitored the Second Boer War and fully supported the Boers against the British Empire. They felt sympathy for the weaker party. Today, not much has changed.

Kosta experiences a strong sense of belonging. Much like it was a century ago, Belgrade buzzes with discussions about global and local politics. Despite Serbia’s limited role on the world stage, international affairs remain an important topic in both the media and casual conversations.

Noticing a strangely dressed man, people from the nearby tables approach him. After overcoming their initial shock at seeing a man who appears to be from the 1900s, they tell him about contemporary Serbia and discuss the problems and dilemmas present in the public sphere. They talk about Serbia’s politics, clientelism, and the overall significance of political parties for personal gain.

“So, nothing changed in this regard”, he replies in wonder.

Just as today, at the beginning of the 20th century, political parties- or at least influential individuals within the upper echelons of politics- wielded excessive power in society. Looking back, Serbia resembled its current state: a society where personal connections could significantly advance one's position in life. Having spent many years abroad, I am well aware that Serbia is not unique in this regard. Yet, it is striking how this was recognized as an important issue in the past, just as it is now; equally, as in the past, there was no quick fix on the horizon.

Furthermore, Kosta learns about the ongoing political crisis. During the conversations, his interlocutors started arguing among themselves about the best way forward. “So, nothing REALLY changed”, he comments in wonder, seeing divisions even among people with similar views. He tells them that in the mid-19th century, a group of young intellectuals sought to create a literary magazine to bridge divisions in Serbian society. Ultimately, they argued among themselves over whether the magazine should publish poetry or prose. Quite symbolic, isn’t it?

After debating with his new friends over who should pay for coffee, Kosta begins his walk with them. He is taken aback by the declining presence of the Cyrillic alphabet in favor of foreign words and phrases. Similarly, he notices the changed role of women in society. He likes that.

Kosta is uncertain about his thoughts on the city's evolution.

He develops a disdain for the prevalent haste. It seems that “everyone is rushing, as if Austrians have decided to invade,” he thinks to himself. “People work too much, it seems”.

He resents the idea of “fast food,” but he loves seeing so many kids in schools. Kids rarely work anymore, at least most of them. It feels strange for him to notice that children do not greet older people on the streets, but he remains silent about it. He likes the enlarged scope of the government and the universal health care.

Kosta notices that people are not dressed nicely anymore. There are no hats, canes, or bow ties. “Everyone is wearing some worn-out bluish trousers and some strange bags on their backs”, he murmured. But the number of really poor people is down, which he happily approves of.

The media shocked him. Everything got bigger and bigger, but the number of daily newspapers went down. They are now printed with oversized, silly-coloured letters, and all the good fonts are gone. They often talk about the country's progress and success, yet people seem to be angry. He was puzzled by this.

In c. 1900, political parties were mostly behind the newspapers. Therefore, buying a newspaper meant you already understood what to expect. Now, it’s primarily wealthy individuals who own them. In 2025, no newspaper makes money; however, in 1900, they lived from subscriptions. He used to give money to support the party he liked. Now, big money means that your voice will be heard, even if it is a minority one.

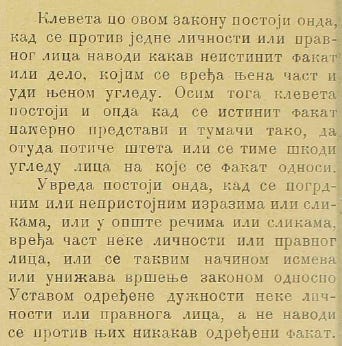

In Kosta’s time, punishment for the editors could have ended newspapers due to its financial severity. In the future he visits, newspapers may continue to disseminate outright falsehoods. Furthermore, even if the court were to render a decision to sanction such a newspaper, the repercussions would be negligible compared to the newspaper’s financial resources. Kosta soon learns about “fake news“.

In this future that Kosta visited, you do not even know who owns what. Back in his time, if you did not write precisely who the editor and the owner of the magazine were, it was a punishable offense.

Moreover, despite intense political conflicts at his time —the names of political opponents were commonly written in lowercase letters in Belgrade magazines—newspapers started to tolerate everything in the 21st century. He tells his new friends that it is a shame that corporal punishment is no longer around. “That would teach some people manners”, he says.

The amendments to the Press Law of 1904 regulating calumny.

Kosta wasn’t surprised to see the university professors in the middle of political strife. When the Belgrade Grand école was renamed to the University in 1905, the majority of the initial eight full-time professors were heavily engaged in politics.

He was shocked that some government ministers in 2025 had fake university degrees, not because some level of morality was lost, but because it seemed that no scandal was big enough to end one’s career in 2025.

He saw students protesting for the first time when the last king from the Obrenović dynasty was in power. Luckily, the police are not that violent now.

He was sad, even depressed, to hear about how the 20th century turned out. He surely hoped for something a bit more peaceful.

His new friends ask, “What period is more democratic?” “Well, women can vote now,” he says, yet the media landscape has changed… “It became easier to hide misdeeds”.

“What mostly puzzles me,” Kosta opens himself fully after a full day of conversations, “is cynicism and apathy. People want to do politics, and yet steer away from party politics”.

“Also, it seems that anti-intellectualism became a thing, huh, guys? I come from a different time; I am a staunch believer in duty, progress, and rational government. I was probably shaped by my time into extreme optimism refuted by what came after me, but you went to another extreme. Here I stand in 2025, in a world bursting with devices that would have seemed alchemical in my youth, and I ask myself: where is the reason?”

“Kosta, you are too much a 19th-century idealist”.

“Perhaps. But everyone, it seems, is their own oracle now—armed with fragments of information, sharp opinions, and a deep suspicion of anyone who knows too much. A bartender just told us that experts cannot be trusted because everyone has an agenda. Facts are treated as outfits one tries on”.

“Kosta, you say everyone is their own oracle now. That’s true. But it’s also inevitable in a world where access to information is no longer gated by privilege, class, or geography. We saw governments lie, corporations suppress data, and institutions protect themselves at the cost of the public. That betrayal bred skepticism. And skepticism, while sometimes corrosive, is also a tool of self-defense”.

“Perhaps, but you are overdoing it. You abuse the freedom. Confidence is not clarity”.

“Reason hasn’t vanished. It’s just learning how to speak in a louder, more chaotic room”.

Kosta likes the comforts of the new age. He could get used to it. He doesn’t really understand what a ‘personal brand’ is, and why so many seems to need one.

“Kosta, do you want to see some fake students camping?”

“Fake…what? And you tell me the reason hasn’t vanished!”